A World Turned Upside Down

Christopher Hill’s history from below.

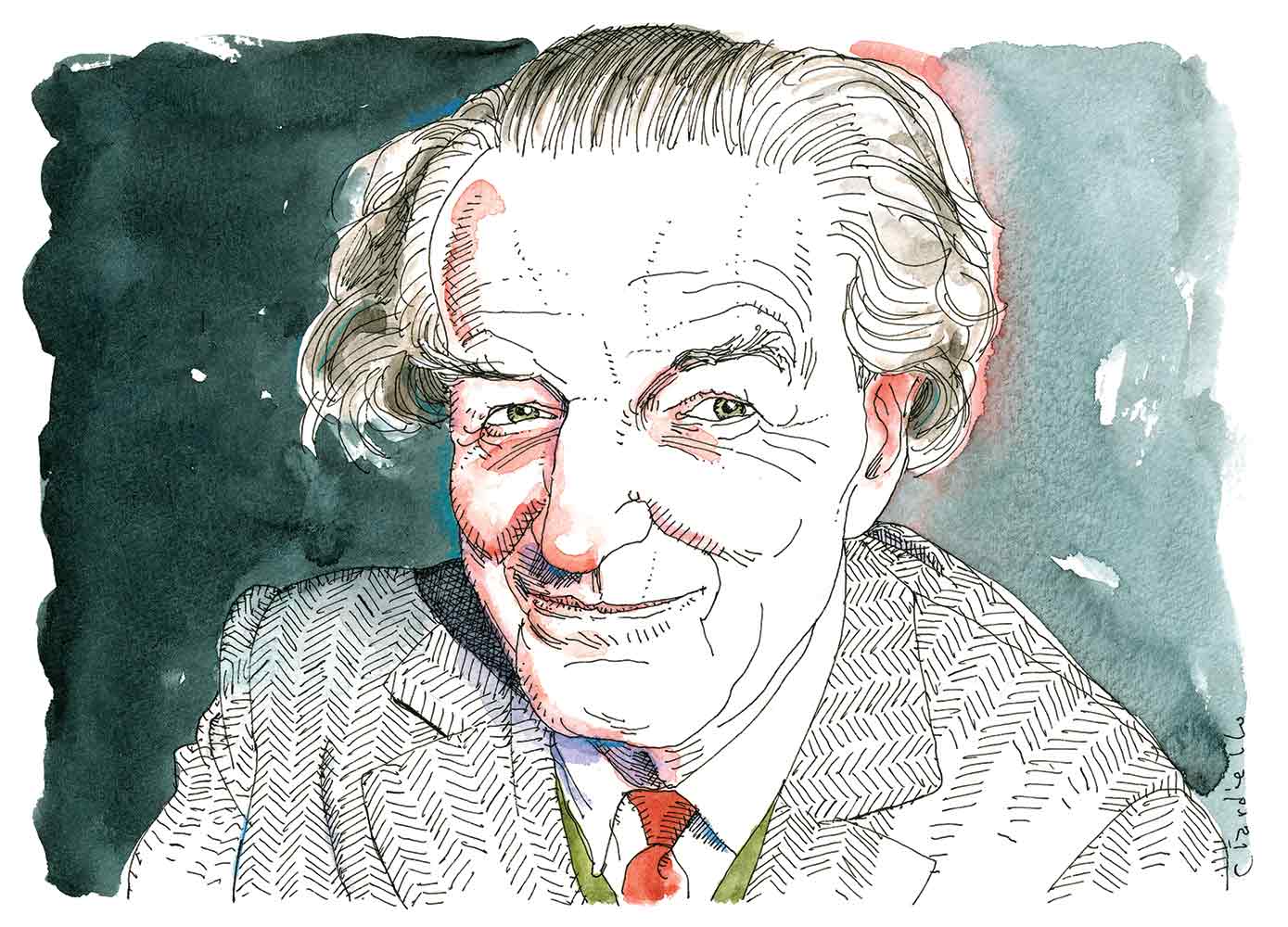

Christopher Hill’s Revolutions

The radical life and work of the historian.

Christopher Hill was one of the most prolific and influential historians of the 20th century. He was also the product of two specific eras of political and social change: the Old Left’s communist and working-class movements of the 1930s and ’40s, and the New Left’s liberation and countercultural movements of the 1960s and ’70s.

At the end of the former, in 1940, Hill wrote The English Revolution 1640, which provided a class analysis of the bourgeois revolution against feudalism and charted a lifetime of scholarship ahead. In the middle of the latter, in 1972, Hill published another book on the same period, his most profound and lasting work, The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution. A social and intellectual history of religious radicals who pioneered the modern ideas and practices of democracy and equality, it was also a book that explored a commoners’ “revolution within the revolution” that, although it failed, nonetheless represented a deep origin story for the history of modern radicalism. Both books, inspired by the movements of their time, helped create the breakthrough that we have now come to call “history from below.”

Books in review

Christopher Hill: The Life of a Radical Historian

Buy this bookOver a career that spanned more than 60 years, Hill wrote 16 more books, dozens of articles, and seven collections of essays. Along the way, he became the leading interpreter of the English Revolution and its broader 17th century. He also covered an extraordinary range of topics, in books from Economic Problems of the Church: From Archbishop Whitgift to the Long Parliament (1956), through Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution (1965), to The English Bible and the Seventeenth-Century Revolution (1993). He offered creative reinterpretations of the writings and thought of John Milton and John Bunyan, linking each as never before to the radicalism of the English Revolution. His breadth of knowledge, his curiosity, his open-mindedness, his love of literature, his command of chronology, and his respect for the humanity of his subjects—all of this was evident on every page of every book he wrote.

Michael Braddick’s new book, Christopher Hill: The Life of a Radical Historian, offers the first full and comprehensive interpretation of his subject’s life, work, and politics. Braddick admits at the outset that the reserved and private Hill “is not an easy subject for a biographer” and that his book is “more an intellectual life than a biography.” Braddick has conducted impressive research in Hill’s papers at Oxford and the thousands of pages of his published work. As a specialist in Hill’s own field, 17th-century England, Braddick brings to the project deep knowledge of the scholarship by both Hill and his critics. His account is shaped by his affiliation with the “revisionists,” led by John Morrill, who over the past 30 years have worked hard to displace Hill as the leading interpreter of the English Revolution, criticizing him for a teleological bias, determinism, anachronism, and his concept of “bourgeois revolution.” But anyone working in this area of history will have prior disagreements given the immense influence that Hill cast upon his particular field and the profession as a whole. In fact, we are hardly impartial ourselves, as Hill inspired our book The Many-Headed Hydra, which we dedicated to him and to his wife, Bridget Hill.

Standing at 5-foot-7, Hill had a sturdy physical presence (he’d been a rugby player in his youth) and a mischievous and ready wit that he often used in self-deprecating ways. He once quipped that he had done a “brave and creditable” job training on a light machine gun for service in World War II, adding: “A thousand pities it was on somebody else’s target.” He also had a stammer, a source of his lifelong shyness and reserve, and described himself as “mean,” by which he meant “cheap.” (His use of pencils endlessly sharpened down to an inch or less was a family joke.)

Hill’s most characteristic trait was his easy egalitarian manner. Former Oxford student Ved Mehta noted that Hill “was singular among dons…that all distinctions of degree, rank, and age were repugnant to him. He was devoid of race prejudice of any kind, and so far ahead of his time that he treated women no differently from men, without a hint of condescension.” Hill’s niece, the historian Penelope Corfield, noted that this commitment to equality, formed early in life, drove his turn toward radicalism in the 1930s.

“If I have roots at all,” Hill once wrote, “it is in the Yorkshire moors.” On those “wuthering heights,” he wandered and cycled. Born in 1912 to a devout Methodist family, he found that those moors nurtured his lifelong egalitarianism. Before him was the landscape of the Luddites and weavers who, a century earlier, had faced the full force of capitalist mechanization at the creation of the industrial proletariat.

As a schoolboy from 1921 to ’25, Hill would cycle the villages to raise funds for the Wesleyan Missionary Society. The Christian mission began a commitment to internationalism that would endure for the remainder of his life. At St. Peter’s school he read Plato, Dante, Goethe, and Tolstoy, wrote poetry in German, and scored the winning try against the school’s rugby rival. He quoted the Methodist pastor T.S. Gregory’s “We are all one in the eyes of the Lord,” as well as the greetings of the 17th-century Ranters: “my fellow creature” or “my one flesh.”

Entering Oxford in 1931, Hill went up to Balliol, the oldest college in the English-speaking world. As a ruling-class institution, it taught “effortless superiority.” In the late 19th century, its master was Benjamin Jowett, translator of Plato and guide to generations of empire builders in the Indian Civil Service. But by 1931, other winds were blowing across its garden quadrangle. A.D. Lindsay, adviser to the Labour Party and the Trade Union Congress, was the master of the college, and he introduced Hill and thousands of others to the famous debates at Putney, where soldiers in 1647—on the verge of mutiny against service in Ireland and for arrears in their pay—debated with Oliver Cromwell and the other “grandees” of the New Model Army, pointing out that every person, even the poorest, “hath a life to live as the greatest he.” Hill was inspired by world history as well as by current events: He was, after all, living in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution and the 1926 General Strike, and amid the massive unemployment brought on by the Great Depression. He set out to see the rest of Europe, traveling to Germany in 1931 and 1933, to Paris in 1932, and to the Soviet Union in 1935.

When Hill arrived in Leningrad in July 1935, he entered a society that was poor but full of hope. Intensive industrialization in the Soviet Union had begun in 1928 and entered a new phase with the second Five Year Plan in 1933. Standards of living were visibly rising, as were the democratic possibilities around a new national constitution, which promised political and economic rights to workers. Hope also beckoned from revolutionary Spain after the formation of the Second Spanish Republic in April 1931 and the general strike of October 1934. An ominous counterpoint was the murder of Leningrad party boss Sergei Kirov in December 1934, followed by a wave of arrests by the NKVD, the Soviet secret police.

During these years, Hill studied Russian and also took an interest in what Soviet historians were writing about 17th-century England, his own focus of scholarship. He joined the Communist Party of Great Britain on his return to England, soon after the Comintern had established the anti-fascist Popular Front strategy that he and many others found appealing.

Hill took a two-year appointment at University College of South Wales in Cardiff in 1936. Referring to the coal bosses and Wales’s two seaports for the coal, the Welsh poet Idris Davies wrote in 1938 (and Pete Seeger sang years later):

Throw the vandals in court,

Say the bells of Newport.

All will be well if, if, if, if

Cry the green bells of Cardiff

expressing a sense of justice and possibility of change. Hill taught the “Puritan Revolution” and showed how an “ancient constitution with common rights” long preceded the monarchy with its “Norman yoke.” He also raised funds for unemployed miners and cared for Basque orphans during the Spanish Civil War, a formative experience: “for 2 years or so,” he would later recall, “these kids really were my life.”

Returning to Balliol to take up a teaching position, Hill began his career as a historian in earnest with the publication of The English Revolution 1640. Even though it was his first major statement on the English Revolution, he would later recall that he “saw it as my last will and testament. I expected to be killed in the war. I wrote it very fast and angrily.” George Orwell attacked the book in the summer of 1940 because, in his view, its implications threatened the mighty structures of the British Empire. But for precisely that reason, it was a work of genius.

The English Revolution 1640 combined class analysis and a new vision of England’s past with a direct address to men and women facing death from the Blitz. And it did so in a language that was easily understood. Hill’s essay was a weapon of anti-fascist war for soldiers like those under Oliver Cromwell, who knew what they fought for and loved what they knew. In its nobility of purpose, its commitment to liberation, and its earnest discovery of the ideas of the oppressed and dispossessed, The English Revolution 1640 might be best compared to W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction (1935) and C.L.R. James’s Black Jacobins (1938). All three are classics of class analysis, dramatic tension, and narrative from below. The historiography was at once social, sociological, and socialist.

In June 1940, Hill went off to world war, hoping to “overthrow all capitalist thuggery, fascist or imperial.” It was a war for the Four Freedoms enumerated by Franklin Delano Roosevelt (freedom of the press, freedom of religion, freedom from fear, and freedom from want), as well as a war of awakening, as Dona Torr taught, for the colonized peoples of Africa and Asia. Expecting to be killed, the young scholar-soldier rubbed his bump of irreverence. As he wrote to Shiela Grant Duff: “Here I am bravely guarding a railway line taking my eyes off the enemy to write to you.” With a wink worthy of the wartime humorist Spike Milligan, Hill irreverently depicted himself as the commander of men digging holes while he took a seat in a pub: He was less good at it than they, he wrote, and they were happy, since “making a hole in the ground is the nearest they ever get to constructive work.” Thus did the 1940s war solve the 1930s unemployment. Hill may have laughed, but then he quoted the early communist and Digger Gerrard Winstanley: “Freedom is the man that will turn the world upside down.”

Upon his return to Oxford, Hill did not abandon his fighting spirit. He played a central role in the Communist Party Historians Group between 1946 and 1953. The meetings included Dona Torr, Edward and Dorothy Thompson, Eric Hobsbawm, Rodney Hilton, Maurice Dobb, Victor Kiernan, George Rudé, Raphael Samuel, and Hill’s future wife, Bridget Sutton. Torr was a major force in the group, pushing it toward history from below—“the sweat, blood, tears and triumphs of the common people”—and helping to form its collective identity.

The group began to create its own division of labor. Dobb had covered political economy in Studies in the Development of Capitalism, published in 1947, so the others could concentrate their efforts elsewhere. Hobsbawm focused on “primitive rebels” and “social bandits,” the Thompsons on William Morris and the early Chartists, Hilton on the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, Kiernan on empire in India, and Rudé on the crowd in the French Revolution. Raphael Samuel would link the Old Left and the New.

As Braddick suggests, Hill consistently warned his colleagues away from determinism, set a serious tone, and demanded high scholarly standards. The meetings had a profound impact; as he later explained, the discussions were “the most exciting and stimulating of any I have ever participated in, unforgettable.” Out of these efforts, in 1952, came one of the world’s premier journals, Past and Present: A Journal of Scientific History, a venue for what would soon be called “the new social history.” Hill led one of the most talented groups of historians ever assembled, and certainly one of the most influential upon the writing of history worldwide after the Second World War.

Braddick rightly emphasizes that the Cold War shaped the reception of Hill’s work in the 1950s and beyond. The way Britain waged it on its own citizens also influenced his life in these years. MI5, Britain’s domestic intelligence agency, began monitoring Hill and intercepting his correspondence in 1935 and continued to do so until 1962. Hill himself noted that he was fortunate to have tenure at Balliol: if not, he explained, “I would have been thrown out in the fifties.”

Meanwhile, within the history profession itself, cold warriors like the American historian J.H. Hexter launched vicious attacks on Hill’s methods and conclusions. Later, in the 1980s, false allegations that Hill had spied for the Soviet Union circulated. In the aftermath of Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin and the invasion of Hungary by the USSR in 1956, Hill and many of his peers left the Communist Party. This did not mark the end of his radicalism, but rather a disavowal of Stalinism and its undemocratic practices. In the 1960s and ’70s, Hill would protest against both the Cold War through the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and the war in Vietnam as he supported radical causes around the world.

Because of his sustained radicalism, Hill never had it easy, but he also gained more and more admirers, both as a historian and a teacher. In 1965, he was elected master of Balliol College. History from below had arrived at the Oxford high table.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Hill’s version of history from below had also evolved. Writing The World Turned Upside Down in dialogue with the transatlantic countercultural movement and freedom struggle of the late 1960s and early ’70s, Hill brought a message from the 17th century to the era’s young radicals: You think you invented the practice of free love, the opposition to imperialist war, the politics of feminism, and the notion of going back to the land? All of that is more than 300 years old! Hill’s account of the Protestant radical groups with wildly colorful names—the Levellers, Diggers, Ranters, Seekers, Fifth Monarchists, Muggletonians, Behmenists, and Quakers—presented a largely unknown chapter of revolutionary history in which ordinary working people seized upon the breakdown of royal censorship, climbed onto laundry tubs to preach in the streets, and rushed into print with a dizzying array of radical ideas and proposals.

Like their heirs in the 1960s, they created not only a protest movement but a counterculture. They variously opposed class privilege, the enclosure of land, wage labor, marriage, poverty, slavery, private property, meat-eating, and empire. Waging a revolt within the revolution, they proposed their own solutions to the biggest problems of the day. Common folk, Hill argued, were not just actors but also thinkers; he wrote their intellectual history from below. In so doing, he inspired scholars, activists, musicians, novelists, playwrights, and filmmakers around the world.

The World Turned Upside Down also drew from a little-known well of inspiration: Norman O. Brown, the classicist and cultural critic. Hill and Brown had been roommates at Balliol. Brown once confronted him, insisting that “you have an absolute moral obligation to join the Communist Party.” Hill added with a smile, “So I did, but he didn’t.” Brown later wrote Life Against Death: The Psychoanalytic Meaning of History, which advocated the pleasure principle and became a classic text in the American counterculture. The book, and Brown’s influence in general, can be found throughout The World Turned Upside Down. Hill even titled a chapter “Life Against Death” and used Brown’s work to rescue the religious radicals of the English Revolution from the “lunatic fringe” to which most historians had consigned them. “The ‘lunatic,’” Hill wrote, “may in some sense be saner than the society which rejects him.”

Hill died in 2003. By that time, he had lived a full life of political engagement and international scholarly distinction. He continued to explore all aspects of popular radicalism and the English Revolution. His books were translated around the world, into Dutch, Russian, Bengali, and Japanese. Later in life, he expanded the geography of his interests, exploring both Atlantic history and liberation theology. In his final book, Liberty Against the Law: Some Seventeenth-Century Controversies (1996), he returned to the theme of antinomian radicalism that had been a centerpiece of The World Turned Upside Down.

In the end, Hill’s knowledge of the 17th century was so vast and deep that outlandish rumors surrounded his reputation—for example, that he had read every primary source published in or about 17th-century England. This, of course, was not true; we know one or two primary sources he had not read. But what is true is that over a lifetime Hill carried out one of the most ambitious intellectual projects of any modern historian: a comprehensive and visionary rethinking of the English Revolution in all its dimensions, from history, politics, and religion to economics, literature, and science. He raised the English Revolution to a level of worldwide significance previously claimed only by the classic revolutions in France and Russia. Deeply specific to the past, Hill’s work was not timeless, and yet what he inspired was. He and his generation of historians encouraged us to think and write about working people not merely as subjects but as makers of history who dared to imagine alternative futures. He taught about the contingencies of history and the creativity of its makers. His hopeful work resonated like a bell on the common wind: “All will be well if, if, if, if / Cry the green bells of Cardiff.”