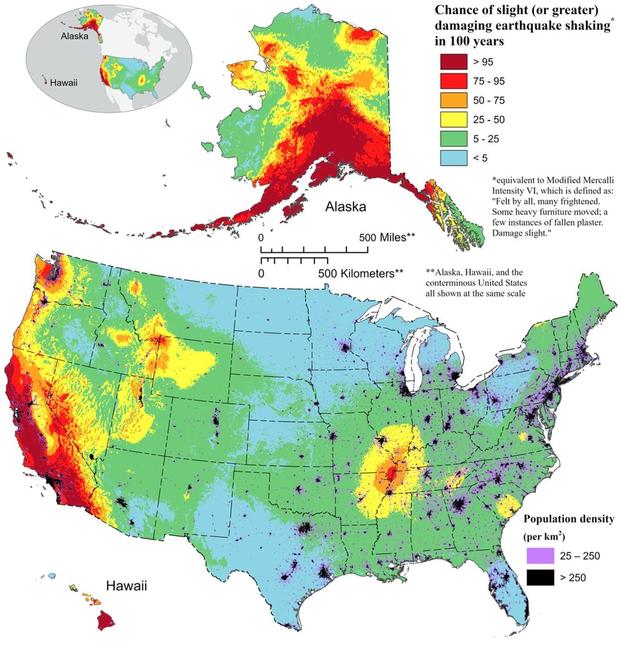

USGS is reporting earthquakes in diverse locations around the United States including in areas that normally don’t see them. While the U.S. West Coast is known for seismic activity, earthquakes can also happen in the Midwest and Eastern states too. Over the last 7 days, in addition to a large volume of earthquakes along the U.S. West Coast, there have also been earthquakes across Texas, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Missouri, New Jersey, Ohio, South Dakota, New Mexico, and Massachusetts.

Earthquakes can be broadly classified into four main types: tectonic, volcanic, collapse, and explosion. Tectonic earthquakes are the most common, resulting from the movement of tectonic plates. Volcanic earthquakes are linked to volcanic activity, while collapse earthquakes occur in underground mines or caverns. Explosion earthquakes are caused by artificial explosions like nuclear detonations. In recent years, earthquakes have also been associated with fracking-related operations.

Fracking

Fracking-generating earthquakes have been a concern in places like Oklahoma and could also become problematic for Louisiana. Beginning in 2009, Oklahoma experienced a surge in seismicity according to USGS. “This surge was so large that its rate of magnitude 3 and larger earthquakes exceeded California’s from 2014 through 2017,” writes USGS in a report analyzing the increase in seismicity here. “While these earthquakes have been induced by oil and gas related process, few of these earthquakes were induced by fracking. The largest earthquake known to be induced by hydraulic fracturing in Oklahoma was a M3.6 earthquakes in 2019. The largest known fracking induced earthquake in the United States was a M4.0 earthquake that occurred in Texas in 2018. The majority of earthquakes in Oklahoma are caused by the industrial practice known as “wastewater disposal”. Wastewater disposal is a separate process in which fluid waste from oil and gas production is injected deep underground far below ground water or drinking water aquifers. In Oklahoma over 90% of the wastewater that is injected is a byproduct of oil extraction process and not waste frack fluid.”

According to USGS, while places like Texas, South Dakota, and even eastern Ohio are not a seismically active part of the country, there are sizeable fracking operations there. According to the Fractracker Alliance, the area of recent seismicity is in an area rich of fracking and oil and gas production.

But not all earthquakes away from the west coast are fracking related, including those along the Mississippi River Valley, the Northeast, and the Southeast.

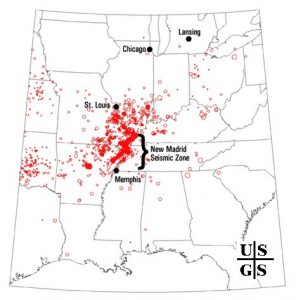

New Madrid Seismic Zone

While the West Coast is also know for intense, damaging earthquakes, another region that could see them is an area known as the New Madrid Seismic Zone, or NMSZ for short. Authorities are concerned that people aren’t properly prepared for when a big earthquake will strike this region. The matter of a larger destructive earthquake in this area is more of a matter of “when” rather than “if.” The NMSZ has a violent history that experts say will repeat itself, although no one is sure when it’ll happen.

December 16 marks the anniversary of the first of three major quakes to strike the United States during the winter of 1811-1812, a violent time in seismological history of the region that scientists say will be repeated again.

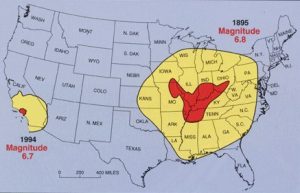

While the US West Coast is well known for its seismic faults and potent quakes, many aren’t aware that one of the largest quakes to strike the country actually occurred near the Mississippi River. On December 16, 1811, at roughly 2:15am, a powerful 8.1 quake rocked northeast Arkansas in what is now known as the New Madrid Seismic Zone. The earthquake was felt over much of the eastern United States, shaking people out of bed in places like New York City, Washington, DC, and Charleston, SC. The ground shook for an unbelievably long 1-3 minutes in areas hit hard by the quake, such as Nashville, TN and Louisville, KY. Ground movements were so violent near the epicenter that liquefaction of the ground was observed, with dirt and water thrown into the air by tens of feet. President James Madison and his wife Dolly felt the quake in the White House while church bells rang in Boston due to the shaking there.

But the quakes didn’t end there. From December 16, 1811 through to March of 1812, there were over 2,000 earthquakes reported in the central Midwest with 6,000-10,000 earthquakes located in the “Bootheel” of Missouri where the New Madid Seismic Zone is centered.

The second principal shock, a magnitude 7.8, occurred in Missouri weeks later on January 23, 1812, and the third, a 8.8, struck on February 7, 1812, along the Reelfoot fault in Missouri and Tennessee.

The main earthquakes and the intense aftershocks created significant damage and some loss of life, although lack of scientific tools and news gathering of that era weren’t able to capture the full magnitude of what had actually happened. Beyond shaking, the quakes also were responsible for triggering unusual natural phenomena in the area: earthquake lights, seismically heated water, and earthquake smog.

Residents in the Mississippi Valley reported they saw lights flashing from the ground. Scientists believe this phenomena was “seismoluminescence”; this light is generated when quartz crystals in the ground are squeezed. The “earthquake lights” were triggered during the primary quakes and strong aftershocks.

Water thrown up into the air from the ground, or the nearby Mississippi River, was also unusually warm. Scientists speculate that intense shaking and the resulting friction led to the water to heat, similar to the way a microwave oven stimulates molecules to shake and generate heat. Other scientists believe as the quartz crystals were squeezed, the light they emit also helped warm the water.

During the strong quakes, the skies turned so dark that residents claimed lit lamps didn’t help illuminate the area; they also said the air smelled bad and was hard to breathe. Scientists speculate this “earthquake smog” was caused by dust particles rising up from the surface, combining with the eruption of warm water molecules into the cold winter air. The result was a steamy, dusty cloud that cloaked the areas dealing with the quake.

The February earthquake was so intense that boaters on the Mississippi River reported that the flow of the water there reversed for several hours.

The area remains seismically active and scientists believe another strong quake will impact the region again at some point in the future. Unfortunately, the science isn’t mature enough to tell whether that threat will arrive next week or in 50 years. Either way, with the population of New Madrid Seismic Zone huge compared to the sparsely populated area of the early 1800s, and tens of millions more living in an area that would experience significant ground shaking, there could be a very significant loss of life and property when another major quake strikes here again in the future.

South Carolina Earthquakes

South Carolina is another area that could see catastrophic earthquakes. According to the South Carolina Emergency Management Division (SCEMD), there are approximately 10-15 earthquakes every year in South Carolina, with most not felt by residents; on average, only 3-5 are felt each year. Most of South Carolina’s earthquakes are located in the Middleton Place-Summerville Seismic Zone. The two most significant historical earthquakes to occur in South Carolina were the 1886 Charleston-Summerville quake and the 1913 Union County quake. The 1886 earthquake in Charleston was the most damaging earthquake to ever occur in the eastern United States; it was also the most destructive earthquake in the U.S. during the 19th century.

The 1886 earthquake struck at about 9:50 pm on August 31; it was estimated to have been rated a magnitude 6.9 – 7.3 seismic event. The earthquake was felt as far away as Boston, Massachusetts to the north, Chicago, Illinois and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to the northwest, and New Orleans, Louisiana to the south. The earthquake energy even traveled as far away as Cuba and Bermuda, where some shaking was felt too. The initial earthquake lasted about 45 seconds.

The 1886 Charleston earthquake was responsible for 60 deaths and over $190 million (in 2023 dollars) in damage. The area of major damage extended out 60-100 miles from the epicenter, with some structural damage even reported in central Alabama, Ohio, eastern Kentucky, southern Virginia, and western West Virginia from the initial quake.

A study published in 2008 in the Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering hypothesized that if such an earthquake were to strike the region today, it would lead to approximately 900 deaths, 44,000 injuries, and damages in excess of $20 billion in South Carolina alone.

The initial earthquake was followed by an aftershock 10 minutes later; over the first 24 hours, seven additional strong aftershocks hit. Over the following 30 years, a total of 435 aftershocks were measured.

But not all earthquakes in South Carolina are tied to the Charleston seismic zone. For the last few years, there’s been an unusual swarm of earthquake activity near Elgin, South Carolina and scientists aren’t completely certain why they are occurring.

On Monday, December 27, 2021 at 2:18 pm in the afternoon, an unusual earthquake struck in this same general area and the quakes have continued on and off since, with dozens reported in 2022, 2023, and 2024. That first 3.3 magnitude earthquake hit 30 miles north of Columbia, South Carolina at a depth of only 3.1 km. More than 3,100 residents reported to USGS they felt it at the time, with one report of shaking coming from as far away as Rock Hill, which is at the North/South Carolina state border. While many felt the earthquake, there was no reported damage in the Palmetto State. That earthquake was followed by 10 more ranging in intensity between a magnitude 1.5 to a magnitude 2.6 event. The second earthquake struck three hours twenty minutes after the first one. The last earthquake in that series struck on the morning of January 5, bringing a temporary end to the earthquakes there. But the swarm returned many times throughout 2022, rattling locals and unnerving local officials that weren’t sure of their source or cause.

According to USGS, a swarm is a sequence of mostly small earthquakes with no identifiable mainshock. “Swarms are usually short-lived, but they can continue for days, weeks, or sometimes even months,” USGS adds. However, the South Carolina event doesn’t fit the typical definition of a swarm since the first event was substantially larger than the rest.

Northeast Earthquakes

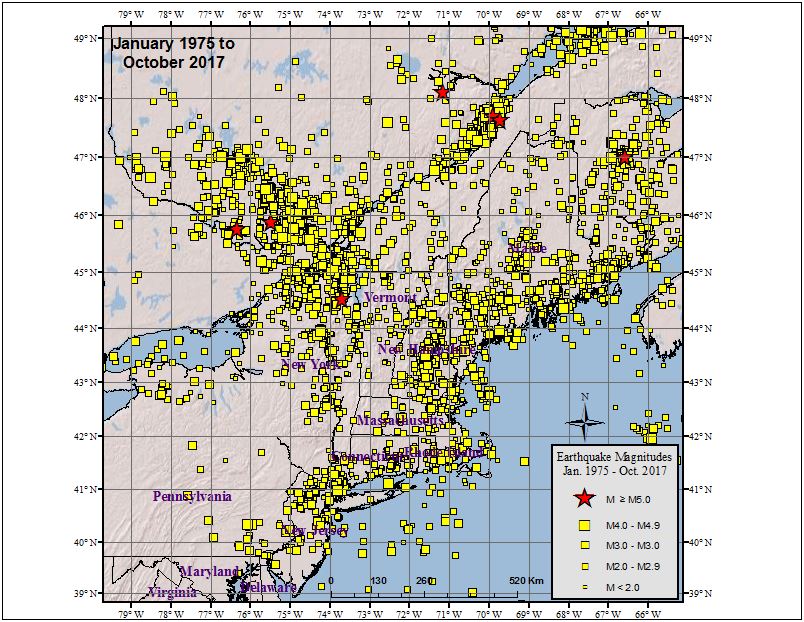

The northeast is also not immune to earthquakes, as earthquakes over the last week in New Jersey and Connecticut show. But even New York sees strong earthquakes from time to time.

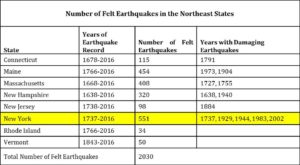

According to the Northeast States Emergency Consortium (NESEC), New York is a state with a very long history of earthquake activity that has touched all parts of the state. Since the first earthquake that was recorded in December 19, 1737, New York has had over 550 earthquakes centered within its state boundaries through 2016. It also has experienced strong ground shaking from earthquakes centered in nearby U.S. states and Canadian provinces. Most of the quakes in New York have taken place in the greater New York City area, in the Adirondack Mountains region, and in the western part of the state.

While many of the earthquakes to hit New York are weak like today’s, some have been damaging. Of the 551 earthquakes recorded between 1737 and 2016, 5 were considered “damaging”: 1737, 1929, 1944, 1983, and 2002.

While most of New York’s earthquakes have been in the Upstate, New York City has also seen damaging earthquakes over the years. At about 10:30 pm on December 18, 1737, an earthquake with an unknown epicenter hit New York with an estimated magnitude of 5.2. That quake damaged some chimneys in the city. On August 10, 1884, another 5.2 earthquake struck; this quake cracked chimneys and plaster, broke windows, and objects were thrown from shelves throughout not only New York City, but surrounding towns in New York and New Jersey too. The shaking from the 1884 earthquake was felt as far west as Toledo, Ohio and as far east as Penobscot Bay, Maine. It was also reported felt by some in Baltimore, Maryland.

Puerto Rico

While the Pacific Coast and its associated Ring of Fire is known for ongoing earthquake activity that occasionally triggers tsunami, Puerto Rico is also seismically active and could also be threatened by tsunami.

Most of the recent earthquakes in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands aren’t far from the epicenter of a strong earthquake that hit in January 2020. That 6.4 created extensive damage in Puerto Rico, including widespread power failures across much of the island. An earthquake swarm started here in December 2019 and unrest has continued since.

These earthquakes are occurring near the northern edge of the Caribbean Plate, a mostly oceanic tectonic plate underlying Central America and the Caribbean Sea off of the north coast of South America. The Caribbean Plate borders the North American Plate, the South American Plate, the Nazca Plate, and the Cocos Plate. The borders of these plates are home to ongoing seismic activity, including frequent earthquakes, occasional tsunamis, and sometimes even volcanic eruptions.

The U.S. Government holds annual tsunami drills for the U.S. East and Gulf Coasts each spring with a variety of international agencies and partners. While Hawaii, Alaska, and the U.S. West Coast are more prone to earthquakes and tsunami, catastrophic tsunami could occur on the east coast too from seismic activity here.